Elizabeth

Dulemba

is an award-winning children's book author, illustrator, teacher, and speaker with

over two dozen titles to her credit, from board books to a young adult novel. She just

competed an MFA with Distinction in Illustration from the University of

Edinburgh College of Art and will begin a PhD in Children’s Literature at the

University of Glasgow School of Education, fall of 2017. In the summers, she is

Visiting Associate Professor in the MFA in Children’s Book Writing and

Illustrating program at Hollins University (Virginia, US). Currently, she is

illustrating a picture book by Caldecott-winning author, Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple, for

Cornell Lab Publishing Group (2018). Learn more at: www.dulemba.com.

My dissertation

objective was to observe similarities and differences between award-winning

children’s book titles from the US and UK to see if trends or cultural

differences could be identified. As an American creator studying in the UK, I

wanted to understand what works in both countries and what doesn’t. By

comparing a decade’s worth of titles from the US

Randolph Caldecott Medal run by the Association for Library Service to Children and the UK Kate Greenaway Medal

run by the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, I learned a great deal about design variations within the two

cultures.

I also located

some aesthetic homogenization through analysing these select titles, finding interesting signifiers in two titles especially that

deserved further exploration. They were Sophie Blackall’s Finding Winnie (Mattick and Blackall, 2015) and Jon Klassen’s This is Not

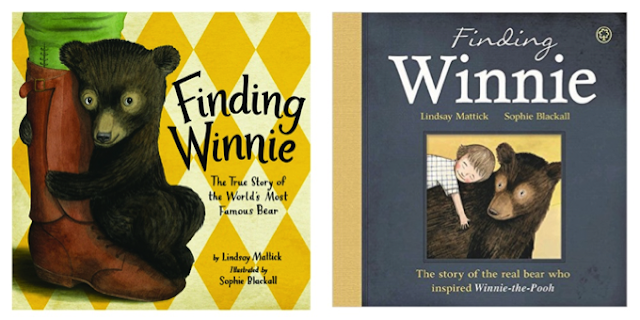

My Hat (Klassen, 2012). We’ll begin with differences between the US cover of Finding Winnie (left), and the UK cover

(right).

Figure 1 & 2 - Covers collected from Amazon.com (US) and

Amazon.co.uk (UK) respectively

Here we can observe

the negative vs. positive space distribution. It is less prominent on the US

cover, where the image takes up more space and Winnie faces and engages the

viewer. In contrast, the UK version has more negative space, with the imagery

neatly framed upon a sombre background, implying distance. As Perry Nodelman

says in Words About Pictures, “…looking

at events through strictly defined boundaries implies detachment and

objectivity, for the world we see through a frame is separate from our own

world...” (Nodelman, 1988, p50)—engagement vs. distance.

This idea is

reflected in the different font treatments and how they place emphasis on

different words within the titles. Both the words Finding and Winnie have

equal weight on the US cover, while on the UK cover, Finding has been allotted less gravitas. Therefore, the US cover

implies that the action of “Finding

Winnie” is the dominant theme, whereas the UK cover implies that the character of “Winnie” is the focal

point—action vs. character.

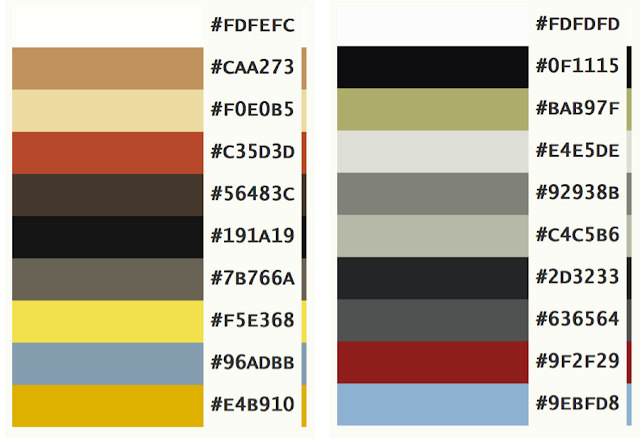

The Finding Winnie covers are prime examples of a key difference

between the two data sets—colour. I combined the ten

covers from each set of titles into one image in Photoshop™ as shown here.

Figures 3 & 4 - Caldecott and Greenaway-winning titles.

I then employed PaletteGenerator.com

to analyse the images, presenting their colour usage through percentage

breakdowns. Here we see the top ten most prominently employed colours in each

conglomerated dataset, the Caldecott palette on the left and the Greenaway

palette on the right—warm vs. cool.

Figure 5 - Palettes created at PaletteGenerator.com

As reinforced in the covers of Finding Winnie, we see two yellows on

the US side, and no yellows at all on the UK side. In Roland Barthes’ “Rhetoric

of the image,” he explains that compared images “… require a generally cultural

knowledge, and refer back to signifieds each of which is global (for example,

Italianicity), imbued with euphoric values” (Barthes, 1977, p154). These two covers exemplify

Americanicity and UKicity between the cultural contexts.

But why is this? As publishing

companies merge and align their publishing goals, it can be assumed that

marketplace differences should be growing less pronounced, leading to an aesthetic homogenization of

cultural content. On the positive side of this idea, Gillian Lathey says, “The ‘language’ of pictures is generally regarded as

international, capable of transcending linguistic and cultural boundaries” (Lathey, 2006, p113). However,

Martin Salisbury expresses concern that “The rich

diversity of artwork from across the globe is increasingly threatened by the

growing necessity for publishers to sell co-editions of their books to other

countries, most importantly the USA” (Salisbury, 2007, p6).

Indeed, crossover

books between the US and the UK have become mainstream. Many top publishing houses in the US, like Penguin Random House, HarperCollins Children’s Books, and Macmillan have offices and headquarters in the UK, or closely

related divisions like Walker (UK) is to Candlewick (US). The US and UK share a

healthy crossover of content and titles with publicity oftentimes aimed at both

countries as they share the same marketing goals. In fact, UK books often rely

on licensed US sales to make a profit beyond their geographically limited

marketplace.

Therefore, it is

surprising that only one book in my dataset proved this homogenization by

remaining identical in both markets, Jon Klassen’s This is Not My Hat (Klassen, 2012), despite being created by a Canadian author/illustrator, picked up

by a US publisher (Candlewick), and sold to their UK counterpart, Walker Books.

As such, we can learn much by analysing this cover:

Figure 6 - This is Not My Hat (Klassen, 2012)

Despite the book’s

popularity, some critics disapprove of the story’s message, a suggestion that capital

punishment is justifiable for theft (“This Is Not My

Hat by Jon Klassen"). It’s

a book that evokes

strong reactions. Perhaps the controversy is one

reason why the book did so well in both markets: it drew attention.

If we look at This is Not My Hat in comparison to the other award-winning titles,

further reasons become clear. The cover design utilises

broad areas of negative space with an anthropomorphized character who is both

distant and looking at the viewer, while in motion. The colour palette has both

a sombre background and bright fish—warm and cool.

This implies that

the separate Americanicity and UKicity of books is diminishing rather than

broadening. Salisbury says, “A tour of the annual Bologna Children’s Book Fair,

for instance, reveals that, at present, UK publishers are deeply conservative

in their use of illustration as compared to, i.e., their French, Italian,

Norwegian, German and Scandinavian counterparts. When asked about this, most UK

publishers will claim that, much as they love the ‘sophisticated stuff’, they

can’t sell it. It is never easy to know who is leading whom here,…” (Salisbury, 2007, p6).

Does that mean

that publishers are intentionally seeking books that will translate into both

US and UK markets without adaptations—that books are indeed becoming

aesthetically homogenized?

When asked what

some of the key differences between the UK and US markets for children’s books

today are, Tessa Strickland responded, “I don’t really see myself as developing

books for the UK and the US; what I notice is that the books attract people

with a certain kind of sensibility, and those people can be anywhere in the

world… there are far more similarities than differences and with very few

exceptions, the same books tend to do well in both markets” (Withrow and Withrow, 2009, p179).

As our markets

become more global in scope, perhaps their separateness is the strangest thing

about them, as books like This is Not My Hat (Klassen, 2012) suggests we may see more crossover award-winners in the future.

Indeed, the most recent UK Carnegie and Greenaway winning titles, Salt to the Sea by Ruta Sepetys (Sepetys, 2017) and There is a Tribe of Kids by Lane Smith (Smith, 2017) were created by Americans.

A recent personal visit to the

Bologna Children’s Book Fair (2016) revealed a vast range in picture books from

around the world, including the US and UK. Certainly, some aesthetic homogenization was

evident; however, overall, distinctly different products were displayed.

Perhaps it’s the diversity of our markets that makes

them so rich and interesting. “As Cotton notes, the picture book is one of the

most accessible means of conveying cultural values; thus it has the potential

to be an effective agent in the dissemination of a sense of respect for the

attitudes of others” (Harding et al., 2008, p9).

In conclusion, we can infer that our

cultural backgrounds influence differences between the two sets of books, but

perhaps more commonality is achieved through the dedication of producing

appealing works in general. Harding sums up the idea

well, “…a good deal of mutual understanding of our different cultures can be

disseminated by the interchange of picture books… In spite of all we have in common,

there is an amazing richness available to us whenever we look beyond our

national boundaries” (Harding et al., 2008, pp9-10).

Bibliography

Barthes, R., & Heath, S.

(1977). "Rhetoric of the image". Image,

music, text. New York: Hill and Wang.

Children’s Books Guide. (2012). This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen. http://www.ChildrensBooksGuide.com

Harding, J., Pinsent, P., International Board on Books for

Young People, National Centre for Research in Children’s Literature (Eds.). (2008).

What do you see?: international

perspectives on children’s book illustration. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars.

Klassen, J. (2014). This

is not my hat. London: Walker Books and subsidiaries.

Klassen, J. (2012). This

is not my hat. Massachusettes: Candlewick Books.

Lathey, G. (2006). The translation of children's literature:

A reader. Clevedon [England]: Multilingual Matters.

Mattick, L., Blackall, S. (2015). Finding Winnie: the true story of the world’s most famous bear. New

York: Little Brown Books for Young Readers.

Mattick, L., Blackall,

S., (2015). Finding Winnie: the true

story of the world's most famous bear. London: Orchard Books.

Nodelman, P. (1988). Words

about pictures the narrative art of children’s picture books. Athens:

University of Georgia Press.

Salisbury, M. (2007). Play

pen: new children’s book illustration. London: Laurence King.

Sepetys, R. (2017). Salt

to the Sea. New York: Philomel.

Smith, L. (2017). There

is a tribe of kids. New York: Roaring Brook Press, Macmillan.

Withrow, S., Withrow, L.B. (2009). Illustrating children’s picture books: tutorials, case studies, know

how, inspiration. Crans-Près-Céligny, Hove: RotoVision.

Congratulations to Elizabeth on completing her MFA! This is such an interesting dissertation topic!

ResponderEliminarThank you, Tina!

ResponderEliminar2018 Bologna Children’s Book Fair will be held from 26th to 29th March as a four-day event in Bologna, Italy. Bologna Book Fair is a highly regarded event, popular for showcasing products and services related to the field of digital media, publishing, and licensing, along with discovering new market trends in children’s book industry.

ResponderEliminarThis is a great post! Paraphrasing is a great way to avoid plagiarism when writing your essays. You can find out more about how this site https://www.paraphraseuk.com/ can help you do just that. Good luck!

ResponderEliminarYoungAngelsInternational is an independednt International Children-Book Publisher. We have marked our presence in international book fairs like Frankfurt Book fair 2018, Bologna Children's Book Fair, London Book Fair, Guadalajara Book Fair

ResponderEliminar